008: Azzedine & the Women Who Made Alaïa, Pt. II

Tina Turner, Naomi Campbell & notes on virality

In countless interviews with Azzedine Alaïa, his confidants and muses, it would seem that one cannot discuss the designer without mentioning the great congregations that took place around the dinner table at his home and atelier, Alaïa's nearest and dearest gathering around meals prepared by him and his chef of many years, Soumaré. Many attribute this to a mythical Frenchness, which seems not to exist in Paris beyond Alaia's domain, others to the designer’s generosity. In a final interview with the designer, documented by British Vogue, much of it revolves around the kitchen, a space outside of his studio where Alaïa came most alive.

Azzedine Alaïa's propensity for nurturing those who walked through his doors, easily preparing meals of couscous, eggs and merguez, or skirt steak with rosemary, for anywhere between ten to forty-five guests at a time reminds me of the habits of my own grandmother, my mother, my eldest aunt, diluting its way down to me (I am more skilled at conjuring food through the press of a few buttons than I am with a skillet, but alas, the intention is well!). My grandparents raised nine children with limited means, and to have a long-distance traveler appear at her doorstep unannounced was commonplace, and through magic we marvel at till this day – she once told me that whatever she put out in the world found its way of returning to her – she would whip up meals that satiated every mouth she had to feed. My mother is the same: on weekends my husband and I see my parents, we are met not with a simple meal but a spread. In cultures where words do not suffice, food is the language of love.

This spirit of immigrant hospitality has ingrained itself within me as well; it is how I honor my family and my heritage, and how I retain warmth in a country where love isn't inherently a shared communal experience. When I read about the moments in Azzedine Alaïa's kitchen and around his dinner table through this lens, I realize that it is indeed the designer's magnanimous spirit that cultivates this atmosphere, but a spirit that has been shaped by his Tunisian heritage and his family. Such degree of hospitality is not uncommon in the households of immigrants, and as the recent history of the Arab region and its people has demonstrated, through struggle and strife, its people have a unique ability to extend themselves to nurture family and strangers alike. This is never conveyed by fashion media with regard to the designer, perhaps because it is in direct conflict with the one-dimensional Western perception of Arabs and immigrants.

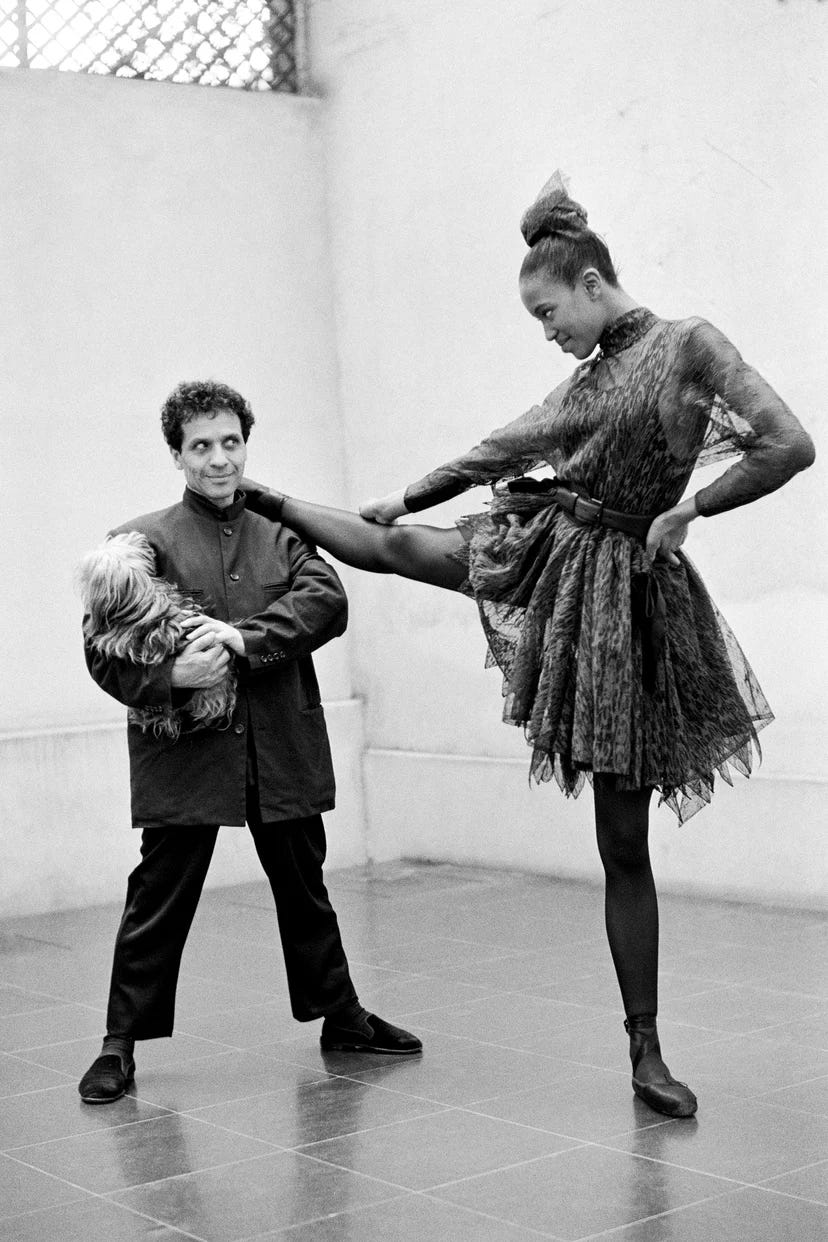

No one has spoken of Alaïa’s gift of hospitality, which extended beyond the kitchen, quite like Naomi Campbell. Campbell lovingly referred to the designer as Papa, more of a father than her own father had been to her. The two were fiercely devoted to each other, and their love has been compared to that of a tiger and its cub. Campbell appeared before Alaïa a teenager of sixteen, newly in Paris and robbed of all her possessions, including her passport. With permission from Campbell’s mother, Alaïa took the model under his wing and raised her as if she were his own daughter for years. When Campbell used to sneak out of Alaïa’s home-studio at night to party at Les Bains Douches – outfitted in Alaïa, of course – and the party had gone on for too long, the designer would set out to bring his surrogate daughter home from the club, doubly irritated if she hadn’t put on her Alaïa outfit the way it was meant to be worn. In the wake of Azzedine Alaïa’s passing, Campbell has been steadfast in her commitment to honoring the designer’s memory, both in his role as a designer and father figure, ensuring that his legacy is never forgotten.

Tina Turner, closing the Alaïa Autumn/Winter 1988/89 show at the age of 48

When Tina Turner first encountered the designs of Azzedine Alaïa in Los Angeles, she had no idea who the designer was but had to meet him immediately. Not long after, she was in Alaïa’s Paris atelier, and a bond of a lifetime was forged. It was during this time that Turner was going through a period of self-discovery and reinvention: she had left an abusive relationship, and her solo album in its aftermath, Private Dancer, was a resounding success. It seems serendipitous that Turner and Alaïa found each other, for she was a brilliant and independent woman who left her mark on generations, and he was the designer who constructed clothes to empower women.

By 1989, Alaïa was designing clothes for Turner’s Foreign Affair album cover, music videos, photoshoots, and the Foreign Affair World Tour. Not one to be boxed in and notoriously rejecting of the fashion calendar, I imagine that pursuing this avenue gave the designer a kind of flexibility the fashion industry is not supportive of, as well as the ability to explore new directions (albeit Alaïa used to design costumes for the dancers of the legendary Crazy Horse in Paris, so creating garments for optimal movement must’ve been a breeze!). Sitting front row at an Alaïa show in 1989, Turner says to the interviewer regarding the designer, “They’re special clothes…the amount of work he put in them for a woman’s body, they’re like anyone else’s clothes.”

Today, one can’t cross a street in Soho (when the weather permits) without a sighting of Alaïa mesh flats. Scroll through Instagram and click your heels thrice, and an Alaïa heart-shaped purse will present itself to you. Witnessing the proliferation of the flats and the purse with such virality made me think about the degree to which the life and works of Azzedine Alaïa, including the devout women who supported him, those who worked alongside him and the art of his craftsmanship, have been mitigated and decontextualized in favor of rapid consumerism. Alaïa famously spurned the traditional fashion calendar and was unafraid to speak frankly about the industry, and eschewed the It: It bags, It shoes.

In virality and It-ness, we overlook the nuances of creations, their creators, and the craft, instead positing bags, shoes, clothes and the like as “stuff”; Alaïa sought to refocus our attention to and appreciation for details. Azzedine Alaia’s legacy sustains because he never once relented, creating considered pieces brought to life by the hard work and limitless imagination of those who gave it form. His clothes were crafted to be timeless, to be fresh and beautiful two or twenty years from now, cultivating a bond with his pieces that cannot be easily severed, even if his house today is the one behind the newest It.

Until next time!

a bit odd to attribute his famous hospitality to 'Frenchness' when it's a well known part of his actual original heritage.

I've always loved that his clothes looked movement-friendly and worked with the female body, it's part of the reason why they don't read cartoonishly shoulderpad-80s to me the way the work of some of his contemporaries from that era (Mugler, Montana) does.