006: Azzedine & the Women Who Made Alaïa

The women of color without whom it would be impossible

While writing my last entry regarding the elevation of the mere mortal's leggings and examining Alaïa's contribution to the cause, I was curious to learn more about the designer himself. Azzedine Alaïa was Tunisian, though much of the press identified him as French first and Tunisian second. He is portrayed as elusive, a great talent who suddenly appeared out of nowhere. Early reviews and brief profiles of Alaïa approach the protagonist with an uncomfortably Orientalist lens. Much commendation is given to the white upper-class Frenchwomen who employed him as an au pair while he was moonlighting as a designer, until a jealous husband decided it was time for him to leave.

During my readings I decided that I wanted to dedicate the next few entries to Azzedine and the women of color who made Alaïa and honor who they were to each other. This entry will be focusing on Azzedine before Alaïa, the designer’s relationships with those of his own kin, from his time in Tunisia into his early years in Paris. The next entry will shed light on the women of his second and third (and final) acts, always holding close the women of his first.

It was here that I was so thankful for the existence of archives, and was reminded of their importance in delineating the stories of people and communities of color, without which we would only know our histories through the white gaze. I was curious to know more about Hafida, Alaïa's beloved sister, whose passing resulted in Alaïa not presenting collections for a stretch of time. What was the significance of the esteemed chanteuse Umm Kulthum to Alaïa, after whom laser-cut clutches have been named? I wanted to know more about the relationship between Alaïa and Tina Turner, who cheekily dedicated her live performance of "I Don't Wanna Lose You" at Versailles in 1990 to the designer; "I'm gonna do this one for...my boyfriend. I call him Azzedine,’ she says. Some answers could be found in drips and dribbles, but the most information I found about Alaïa's legacy and the women of color who made him was – rightfully so – within the archives of Fondation Azzedine Alaïa.

It is virtually impossible to write about Alaïa's background without mentioning the Arab women who raised him and nurtured his talent. Azzedine Alaïa was born to Tunisian wheat farmers Ismaël and Frida in Siliana, but was raised largely under the guardianship of his grandmother in Tunis. He trained at the Tunis Institute of Fine Arts, where he studied sculpture. During his time at the Institute, Alaïa was able to supplement supplies for school by working as a dressmaker alongside his sister, Hafida. Hafida had been educated at Notre-Dame de Sion in Tunis, and gave Alaïa the tools required to build his legacy: she taught him how to sew. Decades later when Hafida passed away, Alaïa retreated from the fashion cycle as he mourned a colossal loss. At the Institute, Alaïa met Latifa Ben Abdallah (née Bach Hamba), his first recorded muse, and it was on her form that he experimented with shapes and techniques which would evolve into the signature styles as we know them today. Alaïa sewed skirts directly onto Ben Abdallah, cinching waistlines to see what effect they would produce.

It was during this time that Alaïa became dear friends with Leïla Menchari, who would later become the Director of Window Displays and of the Silk Colors committee at Hermès over fifty years. Menchari's mother, Habiba Menchari, an outspoken Tunisian feminist activist, held Alaïa's talent in high regard from the very early stages of the designer's career. Habiba Menchari knew a woman who was a client of Christian Dior, and helped Alaïa secure a position at the fashion house (Alaïa was rather unceremoniously let go from Dior just five days after he began work there; questionable claims that were floated include his papers were not in "order", that war had broken out in Algeria, and Alaïa has stated that he was simply never given a reason).

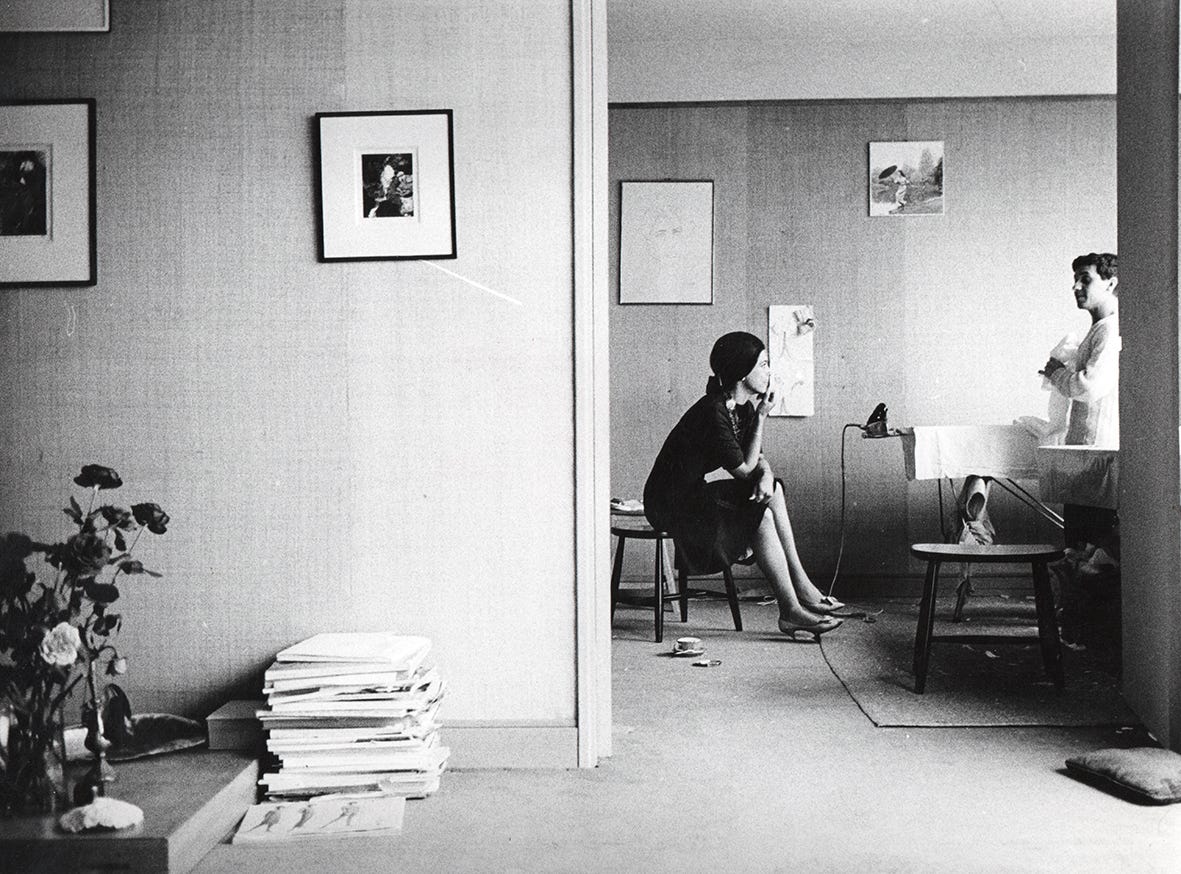

Despite Alaïa and Menchari's enduring friendship – the designer referred to his friend as his soulmate – most accounts of the two (beyond what has been recorded by the Fondation Azzedine Alaïa) neglect to convey how inextricably linked the two were, and would instead seem that they were hardly acquaintances. Soon after their respective moves to Paris, the Tunisian pair shared an apartment and worked at Guy Laroche, Menchari as a model and Alaïa in the workshop. As their careers blossomed, Alaïa and Menchari used their influence and access to promote and support Tunisian craftsmanship.

Azzedine Alaïa was never one to shy away from his heritage, but rather embraced it with outstretched arms. One way in which the designer channeled this was by revering the musical stylings of the legendary singer and songwriter, Umm Kulthum (Oum Kalthoum). Hailed as one of the greatest Arab musicians of all time, Kulthum’s sonorous voice filled the halls of Alaïa’s atelier and ushered models down the catwalk, as heard in the Fall/Winter 1990 show (below). As a child living in Tunis with his grandparents, Alaïa recalled the first Thursday of every month as a time of great anticipation and excitement; dinner was had early and the family gathered around Alaïa’s grandfather Ali as he tried to get radio waves from Egypt. Why? To hear Umm Kulthum sing.

When we talk about Alaïa’s legacy, there has been a tendency to neglect, intentionally or not, the memories and the contributions of the women without whom the designer’s work simply would have been impossible. Arab women – Hafida, Latifa, Leïla – were the blueprint, the foundation of Alaïa. Through exquisite tailoring and construction, Alaïa narrated not only his story, but the stories of those who were formative to him, that of his sister, his dear friends and immense Arab talents, as well as those of his lifelong inspirations and chosen family, such as Tina Turner, Grace Jones, and Naomi Campbell. Alaïa’ sculpted knits endure because they have been imbued with the lives lived of these flesh and blood women. In a fast-paced industry where relationships are at best flimsy, Azzedine Alaïa remained steadfastly loyal to and honored the women of color without whom Alaïa, as we know the brand today, would not exist.

Until next time!

I recently watched that doc The Super Models on AppleTV and started tearing up when Naomi spoke about her beloved, Papa. I cannot wait for the rest of this series!

Thank you for this; I've learned so much!