When I was a teenager, there was a guy who, it seemed, almost every other person of my generation in Dhaka’s tight-knit social circles knew. A diminutive individual who played in a local band, he wasn’t a particularly gregarious person, so where did his notoriety stem from? Part of his allure really came down to, I think, his hair: the shock of pink which stood atop his crown, and from pink it turned red, orange, streaks, sometimes his hair stood upright, and other times hung like a veil. It was a parent’s worst nightmare and the coolest thing someone could do.

To radically alter one’s hair today isn’t high up on the misdemeanor list, but this was the early 2000s and we were all handed a script, whether we liked it or not. The middle-class society I grew up in clung to gendered type-casting and how well we performed them as indicators of our respectability, and boys certainly didn’t dye their hair pink. At the oppressive institution I attended, girls weren’t allowed to dye their hair (which had to be bound) or wear makeup or nail polish. On our last day of school before graduation, most girls showed up with their hair sun-streaked. I think I wore nail polish.

To have a cropped haircut is hardly a revolutionary act: for a little over the first half of the twentieth century, to have short hair was to be en vogue. But on a personal level, my blanket of long hair offered the insurance of my femininity, even on my ugliest days, until yesterday. I walked into to the hair salon I’ve been going to for years near Downtown Brooklyn, took my seat, and to the stylist who has been cutting my hair for all this time, I motioned to the nape of my neck, and said, “Chop it off!” From behind her red-framed glasses, my stylist’s eyes widened. Through the years, she had become privy to my attachment to my hair, my conservative approach to cuts.

As I hurtled into adolescence, unprepared to let go of the child I once was and to occupy this new and unfamiliar space, I became my own worst enemy. I compared myself mercilessly to others, and it was I who always was at a deficit. I looked nothing like taut-tummied, Clearasil-skinned white girls I saw in issues of YM and Nylon my father would bring back for me, at my request, during his sojourns to America for permanent residency, nor did I see myself in the petite, full-lipped, lush-of-hair, wide-eyed stereotype of Bengali beauty. A middle-ground existed, but I couldn’t make space for myself in it. I couldn’t accept myself as an alternative beauty, and so I didn’t see beauty in myself.

I became a hopelessly self-conscious teenager, and grew out my hair to hide behind; if I could’ve grown my hair down to my ankles to seclude my entire being without my mother coming at me with a pair of shears, I would have. At home, my family teased me, telling me that I looked like a folk singer, but at school, all it took were silly boys to tell me that I looked like a boy in my mandated pony-tail – I still can’t tell whether boys love you or loathe you when the behave that way, or loathe to love you – to never want to part with more than half an inch of hair. One time, feeling momentarily brave, I got a shaggy bob of the Friends era, and almost immediately after, prayed, actually prayed to God to restore my hair to its former length.

During my time in Toronto as a university student, I had my hair cut once, unfortunately timed after a breakup. His reasoning was that I was too perfect. Armed with the remaining change from purchasing a week of subway tokens, I headed to Supercuts, and emerged looking anything but perfect, wearing an honest-to-goodness mullet. I hid under a woolen bobble-hat for the entirety of that bleak winter. My best friend will still sometimes shake her head in disbelief at the thought of the relatives I was living with not warning me about Supercuts, where haircuts went to die. I vowed to never cut my hair short again.

When I first started going to the only hair salon I trust, my hair stylist would urge, beg, plead to take off a few inches. Only the split ends, please, I’d insist, and over time she conceded, knowing that I’d never relent to a new height for my hair. Long hair, no matter how dry, damaged and stringy it got, I reasoned, could supplement the absence of beauty or prettiness I experienced. “I don’t feel pretty!” I’ll exclaim to my bewildered husband. “You’re beautiful!” he’ll declare, and I’ll look at him as though he’s stung me with a grave, unforgivable insult. It’s difficult to see oneself in any light other than the harsh florescent spotlight we beam onto ourselves.

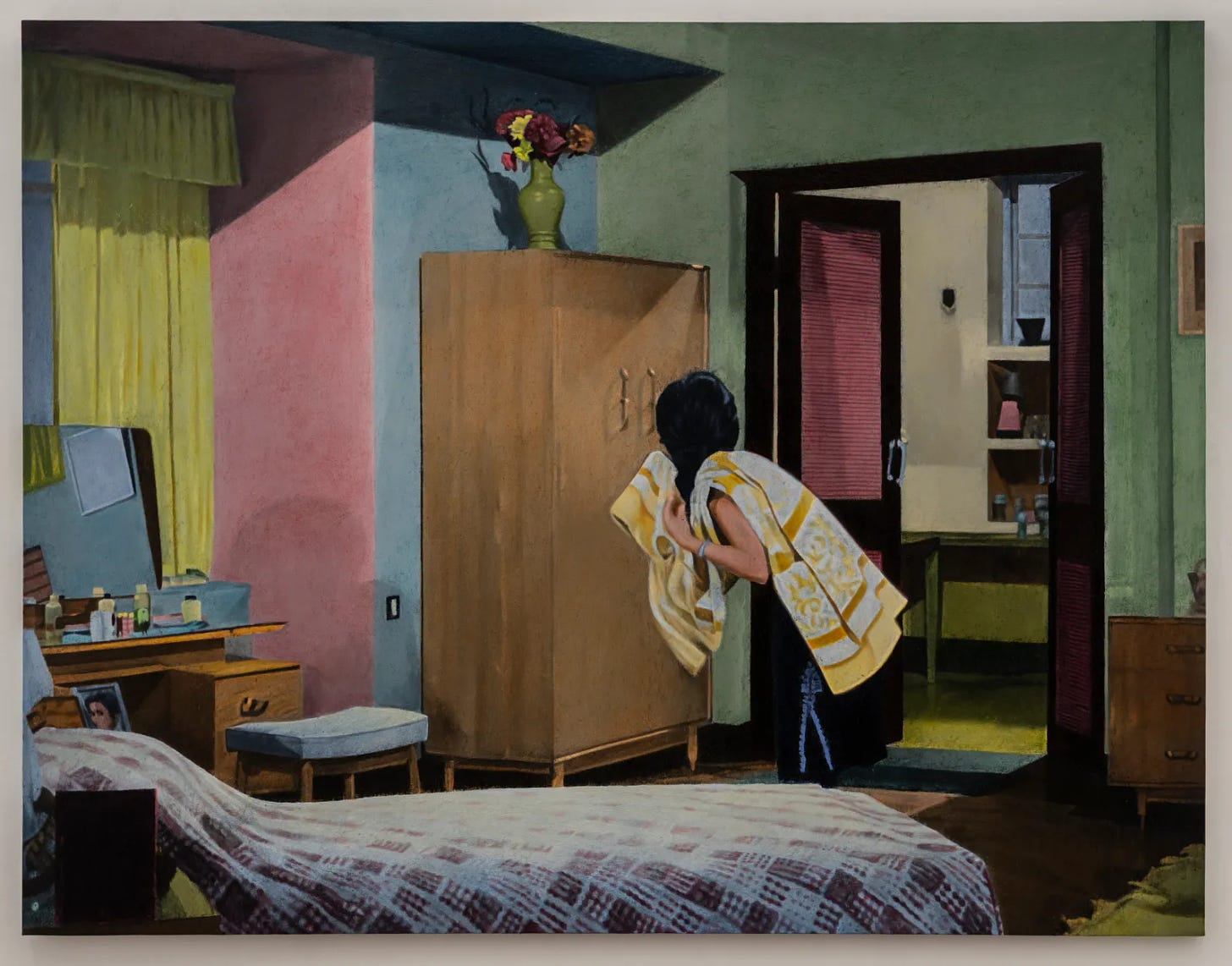

My grandmother had the silver hair of fairytales, the Good Witch, the Noble Queen, into which she’d massage olive oil, pouring it from large cans my aunts and uncles would bring for her from their new homes in new countries into her palms, warming it first. She’d plait it and roll it into a bun, and its feel and scent is what I most associate with home, a shadowy imprint of her hair lingering on pillow cases even after numerous washes, its earthy fragrance holding strong. Just before she passed, her hair had been cut, the first time in a very long time, as it had withered to just a few strands from chemotherapy, our family’s last desperate attempt as we poured our guilt and fear into any means of her survival. Home was lost.

The longer a Bollywood heroine’s hair, the more devastating and acclaimed is her beauty on the beauty metric. The same laws apply to say, a Victoria’s Secret Angel or a categorically Beautiful Woman whose long hair alone can summon a write-up in Vogue. Fingers run through long hair. If your perception of your own beauty is flimsy and you measure yours against that of normative standards, something as inconsequential as hair becomes of paramount importance. It stirs envy, belonging, and longing.

Over the past few months, my hair became a source of restlessness, sitting heavy on my shoulders like a pair of uninspired and entirely artless bookends. Decommissioned anchors. I resisted the impulse to take scissors to it, but it remained a continued source of annoyance. After what has been a not-so-stellar year of personal struggles and the slow unlearning of projected anxieties I had taken on and nurtured as my own, I felt the post-breakup itch to drastically change my hair. A breakup from some of the things that had burdened me, including what my own beauty meant to me.

A shift had taken place. I no longer felt buoyed by my long hair, this matter I brushed daily and knotted so easily, fine and unmalleable, it seemed all too fragile to be so loaded with so much meaning. How bothersome it suddenly quite desperately felt to be so attached to the length of my hair and how I would be perceived by others.

I think I’ll cut my hair short, I said to my best friend and to my husband, without much conviction. On my way to the hair salon, I was still undecided, not convinced that I was ready to part with my internalization of beauty and feminine ideals, but by the time I took my seat, I was certain it was time for a big change. One hand by the base of my throat in a sideways chop motion, as if my hand alone was sharp enough to hack it off. It’s just hair, I told myself, heavy with the meaning I imbued it with.

When the haircut was almost over, I gathered a few stray chunks, seven inches of hair, that had fallen into my lap into a loose ball. It felt coarse between my fingers. I was still myself but a bit different. It felt nice to rid myself of such dead weight.

I took 4 inches off on my last cut. I was just feeling like a change.💕 embrace the change and remember, you can always grow it back.

The wildest thing is that I just chopped off my hair this past weekend. There is something in the air