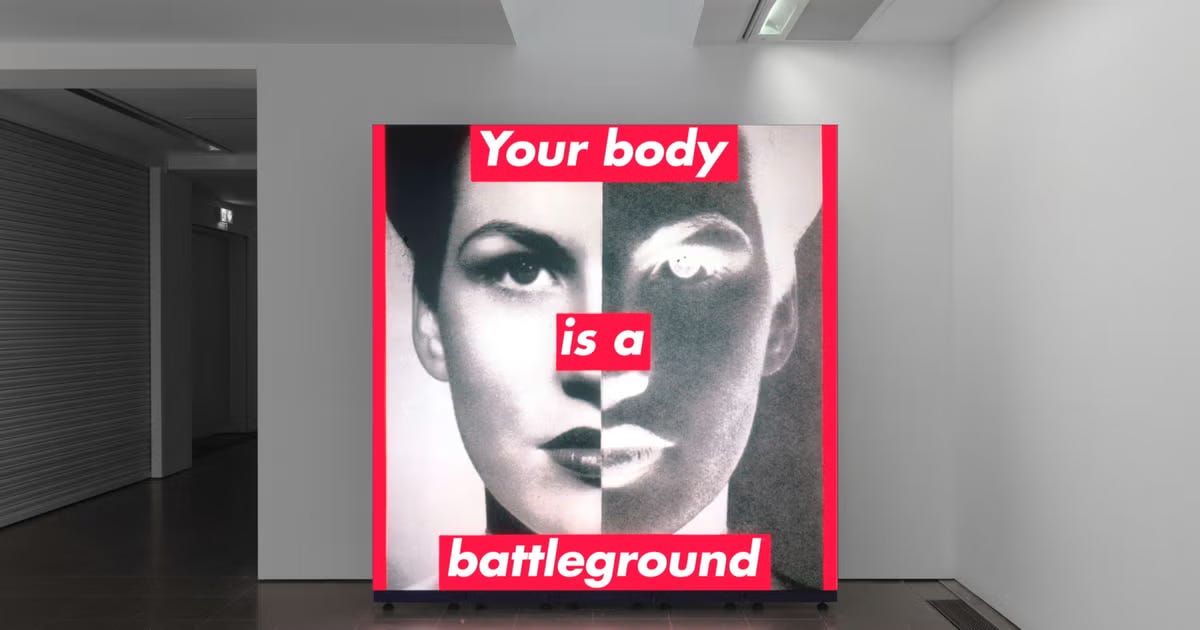

At the age of ten, I first realized my body had failed to meet standards. While trying on a pair of girl’s size twelve blue and white floral jeans in the fitting room of Benetton, I could hardly pull them up and over my thighs, the button closure and zipper unable to meet. From an early age I had been teased by family members about my size – I was taller than older cousins and most classmates, and not as thin as them – but had shelved comparisons to potatoes, pumpkins, balloons and the like with a kind of plucky resilience only afforded to very young children. But on that particular day in that particular fitting room, my mother standing just beyond the curtains eager to buy me a new wardrobe before the arrival of family members from all over for my uncle’s wedding, cousins who wore sizes that corresponded to their ages, I had run out of pluck.

I began to perceive myself as others did: unruly, large, bloated, skin stretched so tight that at any minute I could explode, and what poured out would be endless. Comparisons and jokes at my expense made by those older but no wiser than myself gave way to the development of a ruthless inner critic who had no mercy. I silently compared what I understood as my physical inadequacies with others: the length and width of my thighs compared to my friends’ as we sat side by side, the circumference of my arms to my cousins’, even my mother, and each time I fell short. When I embraced someone, I could only think of how small they felt in my arms and how full and unwieldy I must have felt in their’s, a muscle memory that still revisits from time to time.

When I was eleven years old, I was already on the path to restricting my food intake, hiding what I was given, burying it deep in the trash or flushing it down the toilet. There was a standard to which my body was mercilessly held to, but no tools provided as to how to care for it. There were times I feared my father suspected that I was disposing of meals my parents had spent time and money to prepare, and that guilt consumed me. It wasn’t much later that I had discovered purging; I reasoned the food was at least briefly in my stomach to assuage the guilt. It allowed me to taste all the foods that brought me joy before emptying myself whole.

By the time I turned twelve, I had lost a questionable amount of weight that went unquestioned, and ridicule was replaced by praise, and the praise only made me more scrupulous in my commitment to my eating disorder. The praise cemented within me the belief that my worth, my goodness, esteem, and beauty could only be made possible by my thinness, yet I never thought of myself as beautiful or thin or enough. What I saw in the mirror were only fragments that at only moment could betray me, and elicit an ugliness from adults who should have known better, who themselves had been ill-advised on what it means to be whole.

My eating disorder was my best kept secret. Because I didn’t want to arouse any worry, my objective was not to be too thin, yet another failure we are capable of. To any ordinary person, I was a young woman in a size small, not a young woman who had starved herself into a size small, too afraid to relent the control that put others at ease. And yet it turns out that no amount of control a girl or a woman exacts on her body will ever be enough. The trick is to never heed, easier said than done in a society that conflates appearance with self-worth.

As I entered my twenties, thinness alone could no longer protect me as my body shifted into adulthood. I became aware of my sexuality not independently but because of women – co-workers, relatives, my mother’s friends – around me who were more keen to monitor my developments than I was. There is a special kind of cruelty, informed by internalized misogyny and insecurity, that women can dole out to one another on the matter of how the body should be, and it was from these women that I felt the need to protect my body the most.

It was from them that I had been informed my hips were child-bearing, primed for bearing and birthing children, my calves thick and sturdy; I felt not like a woman but a mule, or a conspicuous grotesque mass when all I wanted was to be unseen. Clothing that outlined my form invited lurid remarks from women who could have been my friends, mentors, North Stars, things I had not seen about myself until I was told: the definition of my hips in a dress, the heaviness of my rear, a particular and disturbing fascination with conventional signs of femininity. I walked stiff as a board, wore compression shorts to hold in all the bits I imagined were spilling out. I regulated myself even when my critics were not around, even when I was free of them in physicality, convinced that what they saw and thought could also be seen and thought by loved ones and strangers.

The year I turned thirty I married my husband, and was naively unprepared for yet another way for my body to fail expectations in my inability to soon become a mother. Relatives eagerly asked when I would give them a grandchild, blessing me with twins. One friend asked my mother when I would have children, couldn’t she urge me as her mother had? And then, earlier this year, rather ironically, I learned that my “child-bearing” hips could not readily bear children. After years of quiet shame and suffering, I was diagnosed with a form of pelvic floor dysfunction that has made conception a prolonged and painful journey.

In all these years of being too much of something and never enough, the exacting demands of my body and desperately trying to neutralize what I now realize were the very fears, envies, and insecurities of those policing my form, I had not learned to care for myself to be whole and healthy, but was well-acquainted with taking myself apart. There was no care in starving and restricting myself, in rejecting myself in the mirror. In that way I was not becoming better or enough, but instead shrinking myself to permit my judges the relief of their short-lived contentment.

How one-dimensional women are thought to be, often by other women, no less. This way it is easier to tear through the center; to allow for complexity, to concede that we suffer, feel pain and pleasure, is to affirm our humanity. Girlhood and womanhood are inevitabilities of being, so natural and commonplace, and yet even for those who have experienced it themselves, there is such a cruel urge to debase and deny what is rightfully ours.

For most of my life, those years that should have been most instrumental and freeing, I possessed a body that had been weighted with definitions and interpretations by those to whom it did not belong. My form had been rendered a site of projected anxieties, reformulated into my own. I have lacked the vocabulary to articulate what my body means to me, to see and accept and love it as it is. Perhaps I will never see myself entirely clearly, perhaps it will never be to me beautiful, perfect, whole, but it is sufficient, for now, to know that my body belongs only to me, and that it is of inestimable worth.

I legit cried when I saw the picture of you

🤍